Economics: An Art Medium

- Leo Pedersen

- Jul 12, 2023

- 8 min read

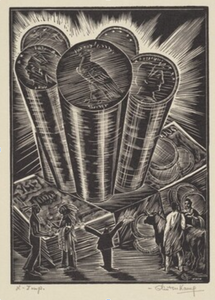

The internet’s four largest art catalogs total to over 1.5 million pieces of artwork. Of course this doesn’t cover every single piece ever made, but it gets pretty damn close and it took me a good while to search through. I started research for this article by trying to find paintings that centered mainly on economics–but out of that one 1.5 million, I was able to find only two and they looked almost identical.

Henry J. Glintenkamp - Money C.1929 | Leon Gordon Miller - Economics Early 1940s |

I guess it turns out that art and economics don’t quite mix. There’s a great wealth of paintings that focus on poverty, or lavishness, class, even on industry. But economics in itself really just doesn’t generate an emotional response, let alone a whole aesthetic. There are a few reasons for this that someone might come up with, maybe it’s because economics happens abstractly and behind the scenes, or perhaps it’s not focused on the natural world. And while these reasons might be true, I think there’s something much more apparent–it’s that none of those mentioned subjects are actually personal to the art world, there’s no other discipline that each and every artist is concerned with as a part of their lives. In other words, art is in a subject relationship to the market, or to making a living–the word most attached to any artist is starving. And in the most abstracted way of looking at it, capitalism could be considered a Medium of art, just like clay or watercolor. Economic conditions determine the way that artists create and showcase their art, and definitely change the way that it’s perceived by the everyday consumer too. And this all in turn leads us to our main question–is modern capitalism a good system for art and its artists? Has the art market just turned contemporary painting into a series of orange squares, or is it something deeply meaningful via this medium?

The first place to turn when considering this question is, of course, the rich. Going through an Art History class, especially up to the 19th century, was pretty much a historical accountance of different types of rich people. Commissioned portraits for a living room, statues for a garden, even icons for a church were all contracted pieces by people with the money; artists creating art without an immediate buyer only happened much later. And even though millionaires and artists seem to be diametrically opposed groups, they paradoxically count on each other–the wealthy buy art for prestige, or for something more sophisticated than a fast car, meanwhile artists need someone to provide their source of income. I came across one study that outlined the incentive structures for people deciding to start art careers, and even though largely unreachable, it projected that just the idea of high market art pricing was enough of an encouragement to start. Just like the dream of big winnings can’t be divorced from even the most casual poker player, every career artist wants value and income to keep doing what they love.

Untitled Markets

But while classic patronage is one thing, modern high-strung capitalism is a whole other beast. If you ask any random person to mention ‘modern art’, they’ll probably cite something that seems incredibly dumb but with an insanely high price. Maybe the duct-taped banana, Banksy, or the famed Orange Square–again if we consider Capitalism as Medium, this aspect may be one of its shades of outcome. Jeff Koons, another modern artist famous for his balloon animals, popularized the word ‘Kitsch’ to describe his work, defined as “In poor taste but appreciated in an ironic or knowing way”. It seems that for a lot of this art, being in on it is a main draw, and for the public it’s since adopted the quality of ‘Meta’, being self-referential to its own weirdness. A lot of people get frustrated about this, saying that the quality of skill has vanished and the only actual interesting thing about these paintings is the price itself. The truly worst part is that most rich people buying these paintings think the exact same thing. Because are they in it for appreciation? No–they’re in it for the money.

Tax deductions through the art market are legal, bizarrely easy, and probably a large part of this whole modern art phenomena. The first step is buying a piece of art, not too expensive but just enough so–let’s say one of Cy Twombly’s Untitled paintings.

He first painted it in 1968, and like many of his paintings, it took less than an hour to complete. Untitled was then bought by Mr. and Ms. Sidney Irmas from Los Angeles, again not for nothing but for pretty cheap while he was still alive. At this point, a new character is introduced–the appraiser. Their job is twofold, first of all to create hype around the artist, then once this is done evaluate the painting to be worth much much more than the price they bought it for. The appraiser might get the artist mentioned in magazines, feature them in other exhibitions, and overall help to create a believable narrative about why it is so meaningful in a societal context. Around this point is when we can see the painting for what it really is–an asset, not much more than a stock or property to buy with expectation that the price will rise.

And it really works, too. Once a set amount of time has passed, or as a morbid truth once the artist has passed away, the billionaire will then donate the piece to a museum or other charity for five or ten times as much they bought it for, all accounting as a tax deductible. In November of 2015, The Irma family donated their painting to a temple in LA for 70.5 million.

But before we delve deeper into what it actually does to art itself, let’s finish our economic analysis of the winners and losers from the above scenario, and to what degree this is actually scamming everybody. We’ve already seen how our given billionaire cashes out by buying a painting and then strategically getting the price to raise. But in reality, the artist gets a really good cut of the deal too–not to mention the given charity or museum. Without this whole process there would be very little incentive for appraisers to lift up an artist’s work, and we’d almost certainly have a lot less artists going around making paintings without the hope of rich buyers. Now of course, the big drawback is that we have a huge tax write off that equates to very real dollars the government could have spent. To total it all up, we get:

Added Value: | Subtracted Value: |

Cy Twombly’s Original Profit (X) +Career Recognition | 70.5 Mil Government Losses from Tax Write-offs |

Irma’s 70.5 Million - (X) | |

70.5 Million to the Given Charity | |

Salary for the Appraisers, Auctioneers, and Overall Added Cultural Value | |

At first it seems like we’ve magically created value! We’re left with double the money, even if it’s going to billionaires instead of the government, that’s still a good thing, right? Especially when it goes to a charity and especially when it helps out the artist? Well, not quite. What we have is a special case of artificially raising value, not actually adding much to the economy. A similar case might be the heavy advertising of something useless like pelotons, or robot vacuums, and everyone rushing to buy them. While it looks great from a GDP perspective, what we got instead was a whole lot of labor going into the building/buying of them and a lot of dead plastic coming out of it. Similarly, in the end of all this we get the same amount of money through a tax write off, and a 15 minute painting donated to a cause that really can’t do much with it. Or a museum with a new painting that very few people would actually want to see. Perhaps some people did really like his paintings, and his level of creativity really was worth a lot to them, but as with a lot of modern art, most likely not.

‘The Courage to Be An Absolute Nobody’

One of the recent movements that showcases “capitalism as medium” was called Zombie Formalism, peaking from about 2010-2017. Most of the artists involved were usually pretty young, and the majority of the paintings fell under some amorphous umbrella of “abstract expressionism”. Usually minimal, with no clear subject, large canvases but not much going on. Artists will try to create interest by doing something like ‘the world’s first painting with a fire extinguisher’, but in reality meaning nothing and covering it up with a long-winded backdoor justification. But even these piece descriptions are usually mind-bogglingly abstract without saying much at all. Twombly’s Untitled was described by Sotheby’s auction house as : “Investigating the definition and physical nature of a simple geometrical element in space as it erupts within the picture plane with cataclysmic graphic narrative, pulsing with an ineffable rhythm.” Seemingly saying a lot but really meaning nothing at all.

Now, not only did Zombie Formalism dull the advancement of art, it definitively marked the height of art flipping. Instead of considering the investment in an art piece something slow that will take time, buyers would often flip these paintings in the span of a few years. Actually, after any given artist would be given the limelight for a while the value of their paintings would then go down just as sharply as they went up. This all had the effect of commodifying an artist’s career–again treating them like a stock instead of someone creating cultural value.

It’s no surprise either that this decade saw a lot of people taking their faith out of modern art. Even when people tried to rebel against this system, it got equally sensationalized and turned into capital. Banksy might be a foremost example of this by famously shredding his auctioned painting, only causing the value of his work to go up even more. It also trickles down to many other parts of culture–my mind goes to the slew of books like “The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck”, or how most pop bands get labeled as ‘alternative’. Rebellion has been such an inherent and important characteristic of art throughout all of art history, yet no other system has been able to disempower that as much as modern marketing.

Well, disempowered to a point. The author J.D. Salinger phrased it as, “I'm sick of not having the courage to be an absolute nobody”. Banksy’s rebellion of shredding his painting at auction increased his capital–so in a way, his stunt belongs to the art world and its desires just as much as the next painting does. Of course there’s nothing wrong with that, but if he wanted a truer rebellion, he probably could have stopped selling to rich people all together. And honestly I think that rule could be applied to most artists–their skill can still be revolutionary and disobedient as long as fame or money isn’t their biggest appeal. Unsellable punk music, craft fair soap, or film festival one-offs are still bought and sold, but don’t feel like they belong to any economic system. Even to those who did make it big, there are people like MF Doom who kept an anonymous cool through his mask, or Lin-Manuel Miranda who donated huge portions of his income to causes like immigration. These people bring us a lot of joy and if anything, this new age of modern art has shown us that above all we should put value in where we see merit, not where we see money.

Earlier in this article we drew up a table of the winners and losers of the art market, and were confronted with this “Ghost” of created wealth equal to the new price of the painting. And while that new monetary value may not be tangibly useful to say an environmental charity, it still gives us something to look up to. I personally love going to museums, and very rarely have I had the feeling of looking at dead pieces of canvas–instead, a lot of high art evokes a strong response from many different people. Everybody reading may be able to create a fire extinguisher painting, or even a Cy Twombly piece, but very few can make a Klimt or Dali. These paintings are the perfect example of ‘something to look up to’, a safe place to put deep thought collectively–and that means something. If recent trends in the art market have caused itself to turn disingenuous, so be it, and it makes sense that people should turn to other places to appreciate different types of art. But as long as there’s space for rebellion, and as long as there are genuine people, it will take much more than market coercion to stop good art.

Works Cited

"CY TWOMBLY - UNTITLED. NEW YORK CITY 1968." ArtsCash.com, artscash.com/paintings-65.html. Accessed 10 July 2023.

"The Economics Of The Art Market: Why This Painting Isn't Worth $450 Million." Youtube, uploaded by Economics Explained, 31 May 2020, www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5sOuET8UWA&ab_channel=EconomicsExplained. Accessed 10 July 2023.

"Is Art Meaningless? | Philosophy Tube." Youtube, uploaded by Abigail Thorn, 19 Aug. 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6EOVCYx7mY&t=1939s&ab_channel=PhilosophyTube. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Pierson, Matthew. "Art in the Age of Tax Avoidance." SSRN, 23 Mar. 2023, papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4391036. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Comments